Kansas City, Missouri

Kansas City Star Building image courtesy Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, MO. Used by permission.

Steve Paul (Independent Scholar) and Dr. Hilary Justice (JFK Library).

All newspaper excerpts courtesy The Kansas City Star. Used by permission.

Updated 11/2023.

Kansas City Timeline

1917-1918: The Apprenticeship

Summer, 1917: After graduating high school, Hemingway considered his options while spending the season at Walloon Lake and Horton Bay, Michigan. An uncle offered to land him a job in the newsroom of the Kansas City Star; he resisted but was at least partly swayed by a friendship developed at Horton Bay with Carl Edgar, who worked for a fuel-oil company in Kansas City.

Oct. 17, 1917: Hemingway began working as a reporter-in-training at the Star, an influential and widely read newspaper with morning, afternoon and weekly editions. His earliest daily assignments usually involved writing brief obituaries, editing a letters column, and gathering crime news. Hemingway stayed four days at the Warwick Boulevard home of Alfred Tyler Hemingway and his wife, Arabell, then moved to a boarding house a block away.

Oct. 24, 1917: The newspaper’s front page reported on the Austro-Hungarian attack in northeast Italy and the retreat of Italian forces at Caporetto. More than a decade later, Hemingway, would frame his novel A Farewell to Arms around this historical moment.

Nov. 17, 1917: Hemingway interviewed Theodore "Ted" Brumback, who had just returned to his hometown after serving nearly five months in the ambulance service in the war zones of France. The two became friends.

December 1917: Hemingway moved from the Warwick rooming house to 3516 Agnes Street, near the Prospect Avenue streetcar line. He shared a third-floor room with Carl Edgar and remained there until he left Kansas City the next May.

December 16, 1917: Two months after he started work, Hemingway's first full-fledged feature story appeared in The Star. The piece, "Kerensky, the Fighting Flea," combines Hemingway's love of boxing with his lifelong tendency to undercut the prejudices of his time with a gut-punch of basic humanity. This feature story, which appeared on the last day of Hannukah, concerns an aspiring young pugilist named Leo Kobreen, a Star newsboy, who was under five feet tall and a successful amateur boxer. Kobreen was a Russian immigrant; his nickname "Kerensky" refers to the former Russian Prime Minister Alexander Kerensky who had recently fled into exile after the Bolshevik revolution.

February 1918: Brumback, by then working as a Star reporter, and Hemingway intercepted a wire service story about the recruitment of Red Cross ambulance drivers for service in Italy and applied to join.

April 16, 1918: In a letter to his father, Hemingway boasted of his accomplishments at the Star and conceded that the work had worn him out: “I have had a lot of valuable experience and have done some good work and have hit it pretty blame hard. And now Pop I am bushed! So bushed that I can’t sleep nights, that my eyes get woozy, and that I am losing weight and am tired all the time. I’m mentally and physically all in, Pop.” He complained about the newspaper’s pay scale and suggested that after a fishing trip up north, he’d be looking for jobs elsewhere. He made no mention of signing up for the ambulance corps in Italy.

April 23, 1918: Hemingway was subpoenaed by a federal judge to testify before a grand jury hearing a case relating to a story he had covered in January. It’s unknown whether he, or another police reporter for the Star who was also on the witness list, actually testified.

April 30, 1918: Hemingway's last day at the Star. He left the next day for Oak Park with plans for a fishing trip to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

World War I

May 8, 1918: T. Norman Williams, who helped train Hemingway at the Star, writing from a new job in St. Louis, encouraged him to take a typewriter to the war and to send back dispatches to the newspaper. His praise for the young man’s talent is effusive:

“You see things. You know things. You read people like a book. And above all you can tell it.”

– T. Norman Williams

May 13, 1918: The Star reported on Hemingway and Brumback’s departure for the ambulance service in Italy. The illustrated item mistakenly identifies Hemingway as 19; he was still 18, more than two months away from his next birthday.

July 14, 1918: The Star reports on Hemingway’s wounding, “the first casualty to any of The Star’s 132 former employees now fighting with the Allies.”

1928

June 14, 1928: Hemingway and his second wife Pauline arrived in Kansas City for the birth of their first child, Patrick, who was delivered at Research Hospital after a long labor. While in Kansas City, Hemingway wrote as many as 175 manuscript pages of A Farewell to Arms; sent updates about his ailing wife and newborn son to his parents in Oak Park; and briefly attended the Republican National Convention, though he concluded (in a letter to Waldo Peirce), “The convention was too shitty to write about.”

June 28, 1928: Birth of Patrick Hemingway to Ernest and Pauline Hemingway.

July 30, 1928: Bill Horne, a Chicagoan whom Hemingway met while traveling to Italy for service in the Red Cross, joined Hemingway in Kansas City, from which they took a three-day drive to a mountain resort near Big Horn, Wyoming.

August 18, 1928: Pauline Hemingway joins Ernest in Wyoming.

Sept. 24, 1928: On their way back from Wyoming, Ernest and Pauline Hemingway stayed briefly with his aunt in Kansas City. (After the untimely death of Uncle Tyler Hemingway four years earlier, Arabell had married architect Clarence Shepard, who had designed their new house at what is now 55th Street and State Line Road.) The Hemingways soon proceeded to Pauline’s family’s home in Piggott, Arkansas.

The early 1930s

October 14, 1931: Hemingway and Pauline returned to Kansas City for the birth of their second child, Gregory, again at Research Hospital. In Kansas City through early December, Hemingway reported finishing work on Death in the Afternoon (except for assembling the appendix material).

November 12, 1931: Birth of Gregory (later: Gloria) Hemingway to Ernest and Pauline Hemingway.

April 1932: Raymond B. “Bud” White, a Kansas City cousin, and his wife, Helen, visited the Hemingways in Key West. Bud White shot a short film of their eight-day fishing excursion aboard Captain Joe Russell’s boat, the Anita.

The late 1930s

June 2, 1936: A correspondent for The Kansas City Times (the morning edition of the Star) wrote about how Hemingway had turned Key West, Florida, into a literary mecca: “Everybody in town knows where Hemingway lives, and all about him. He is popular with the townsfolk and mixes with them freely. He detests formal society and ducks the conventional colonies that revolve around the winter hotels. At the moment he is working on a novel dealing with the contemporary scene…”

Dec. 6, 1936: Ted Brumback recounted his journey to the war with Hemingway in a feature article for the Star: “With Hemingway Before ‘A Farewell to Arms.’”

July 11, 1937: The Star reported that Hemingway touched down at the local airport the night before in a TWA sleeper plane while traveling to Los Angeles for finishing work on The Spanish Earth: “Asked how long the war in Spain would last, the famous correspondent predicted at least another year. He said he was returning to the front in three weeks. His dispatches written for the North American Newspaper Alliance, are printed in The Star.”

1940

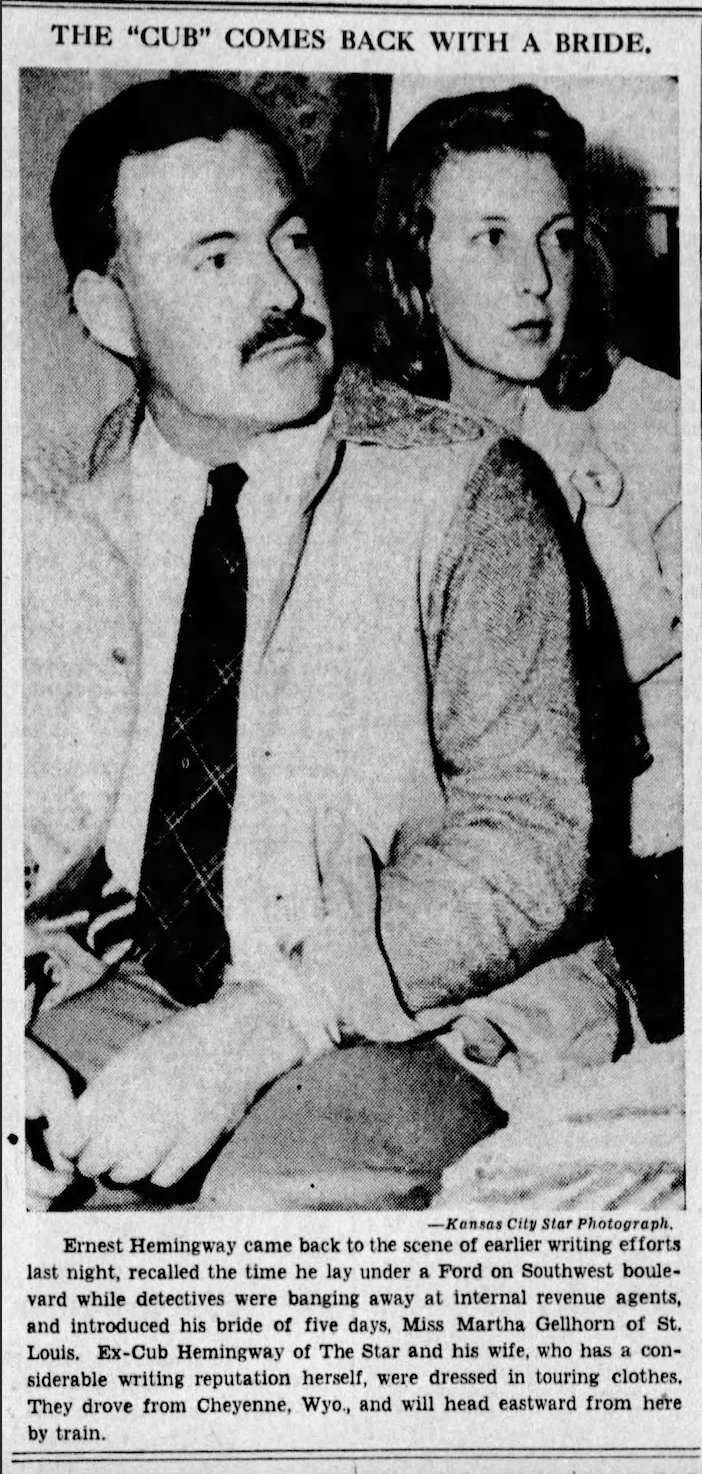

Nov. 25, 1940: Four days after their wedding in Wyoming, Hemingway and his third wife, Martha Gellhorn, stopped in Kansas City for a brief visit while on their way to New York. A Star reporter paid a visit and wrote a Page 1 story for the morning Times about the celebrated author’s return to “his first field.”

Their November visit included a meeting with the Spanish exile artist Luis Quintanilla, who was spending that academic year in residence at the University of Kansas City (now the University of Missouri-Kansas City), where he painted a series of frescoes.

Kansas City Relationships

Alfred Tyler Hemingway and Arabell White Hemingway (Shepard)

Uncle Tyler (1977-1922) was Dr. Clarence (Ed) Hemingway’s brother and worked for a major lumber company in Kansas City. His college connection to a top editor at the Kansas City Star led to his nephew’s job opportunity at the paper. Arabell (1976-1963) was the daughter of a prominent businessman (and Tyler’s boss); her nephew Raymond B. White would maintain a long friendship with Hemingway.

Theodore "Ted" Brumback

Theodore "Ted" Brumback (1894-1955), son of a prominent Kansas City judge, spent the summer and fall of 1917 in the ambulance service in France. After his return, Brumback re-entered the local real estate business, but spent some time reporting for the Star and notably contributed an extended narrative account of his ambulance experience. He and Hemingway signed up for the service in Italy and traveled together to the war. Brumback’s father died by his own hand; when he heard of Clarence Hemingway's December 1928 suicide, Brumback consoled Hemingway by letter.

Luis Quintanilla

Artist Luis Quintanilla (1893-1978) met Hemingway in Spain in the 1920s and drew his loyal support while serving jail time as a political dissident in the early 1930s, before the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. Hemingway contributed a testimonial for a Quintanilla exhibition and the preface for a book of the artist's wartime sketches. Later that decade, Quintanilla worked in exile in the U.S., completing murals for the 1939 World’s Fair in New York and for Kansas City University in 1940-41.

Dr. Don Carlos Guffey

Dr. Don Carlos Guffey (1878-1966), an obstetrician and book collector, delivered Ernest and Pauline Hemingway's children Patrick and Gregory and received gifts of signed books and manuscripts from Hemingway, which he later sold.

Dr. Logan Clendening

Kansas City physician Dr. Logan Clendening (1884-1945) was well-known for his nationally syndicated columns and books on health matters. Hemingway borrowed from an incoming letter to Clendening to create his short story “One Reader Writes.”

Works Set in or Inspired by Kansas City

"chapter 9" of the Paris in our time (1924) is a brief, newsreel-type account of a pair of cigar-store burglars. The account borrows from a true Kansas City crime, which Hemingway helped cover for the Star.

In The Sun Also Rises (1926), the central character, Jake Barnes, is a former Kansas City newspaper reporter.

“The Ash Heel's Tendon.” This early short story was probably written in 1919 in Petoskey, Michigan. It appears to be set in Chicago, but two Kansas City details demand attention.

- The policeman in the story is based on a real-life Kansas City officer, Jack Farrell, who figured into the cigar-store story (above) by shooting one of the perpetrators.

- In the story, Hemingway credits the title to his fictionalized version of Farrell, who came up with the phrase, suggesting that every criminal gunman has a weakness, or "Achilles heel" (tendon).

The story was first published in Peter Griffin’s biography Along with Youth: Hemingway, the Early Years (1985).

“A Pursuit Race.” A burlesque show advance man, a bed-ridden heroin addict, is confronted by his boss, the burlesque show manager, in a Kansas City hotel. (Somewhat related to this, as well as to the next item, is an unpublished manuscript fragment about a Kansas City doctor who was also a narcotics user [EHPP-MS50-042, item 471].)

“God Rest You Merry, Gentlemen.” This stark, Christmas-time story begins with a curious observation connecting Kansas City’s landscape with Constantinople. The story then follows a reporter to a visit with two emergency room doctors. Their cases that night include a young man who wants to be castrated.

“One Reader Writes.” Hemingway essentially transcribed a letter sent to Dr. Logan Clendening of Kansas City, who wrote a nationally syndicated column on health.

In Across the River and into the Trees (1950), Col. Richard Cantwell has pleasant memories of his time in Kansas City and playing polo at the Country Club, a sport Hemingway had viewed there in 1928. Cantwell tells his lover, Renata, that they would someday drive to Kansas City on their way out West and stay at the posh Muehlebach Hotel, “which has the biggest beds in the world.”

A Moveable Feast (1964), the Paris memoir Hemingway drafted in the years before his death, finds him revisiting Kansas City in at least two recollections. In recalling a conversation with Gertrude Stein about sex and homosexuality, he writes, “I knew many inaccrochable terms and phrases from Kansas City days and the mores of different parts of that city, Chicago and the lake boats.”

Stein had warned Hemingway against publishing his story “Up in Michigan” because its sexual content made it "inaccrochable": unacceptable to mainstream sensibilities.

Hemingway uses his inaccrochable Kansas City memories later in the book while describing a café lunch with Ernest Walsh during which they ate oysters and drank Pouilly-Fuissé. In the memoir, Hemingway deploys some word play while wondering if he’s being conned by Walsh or whether his lunch companion is dying of consumption, called the “con,” which launches him into this odd (and, for the time, inaccrochable) memory:

“I was wondering whether he ate the flat oysters in the same way the whores in Kansas City, who were marked for death and practically everything else, always wished to swallow semen as a sovereign remedy against the con; but I did not ask him.”

Works Written in Kansas City

During his six-and-a-half-month apprenticeship period at the Kansas City Star, Hemingway wrote numerous journalism articles. Many of the most notable feature articles, including “Kerensky, the Fighting Flea,” “At the End of the Ambulance Run,” and “Mix War, Art and Dancing,” contain elements of narrative, detailed observation, and dialogue worthy of the writer-to-be. The first two of those stories are included in an appendix to Hemingway at Eighteen, along with a military-recruitment feature, “Would Treat ’Em Rough.” (Many of Hemingway's Kansas City Star stories are collected in Ernest Hemingway, Cub Reporter [1970].)

According to his periodic reports in letters, Hemingway wrote at least 175 manuscript pages of A Farewell to Arms (1929) before and after the birth of son Patrick in June 1928. Pauline Hemingway’s long labor and difficult delivery gave Hemingway some fodder to deploy imaginatively at the end of the novel. Within weeks, Hemingway left Kansas City for an excursion to Wyoming, where he completed the draft of the novel in September.

In 1931, while in Kansas City for the birth of his youngest child, Gregory, Hemingway completed writing the main text of Death in the Afternoon (1932). As he reflected on regularly greeting sunrises in Madrid and Constantinople, Hemingway worked in a Kansas City memory: while driving back to his cousins' house after attending the Republican National Convention, he saw what he thought was a fire on the horizon, which reminded him of the 1917 Kansas City stockyards fire. He realizes that he is seeing the sunrise and that he has once again stayed up all night.

One undocumented account of Hemingway traveling through Kansas City in 1939 has him writing passages of For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940) while waiting for bad weather to pass during an airport stopover.